The transcript of Dialogos Radio’s interview with scholar and analyst James Petras, professor emeritus of sociology at Binghamton University in New York, who spoke to us about his experience serving as an adviser to Andreas Papandreou, on the Papandreou family and its role in the destruction of Greece, and on his thoughts regarding Greece’s new SYRIZA-led government. This interview aired on our broadcasts for the week of April 2-8, 2015. Find the podcast of this interview here.

The transcript of Dialogos Radio’s interview with scholar and analyst James Petras, professor emeritus of sociology at Binghamton University in New York, who spoke to us about his experience serving as an adviser to Andreas Papandreou, on the Papandreou family and its role in the destruction of Greece, and on his thoughts regarding Greece’s new SYRIZA-led government. This interview aired on our broadcasts for the week of April 2-8, 2015. Find the podcast of this interview here.

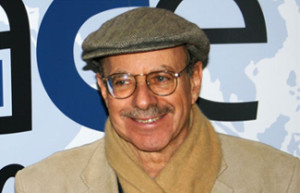

MN: Joining us today on Dialogos Radio and the Dialogos Interview Series is James Petras, professor emeritus of sociology at Binghamton University in New York, former adviser to political figures such as Andreas Papandreou in Greece, and Salvadore Allende and Hugo Chavez in Latin America, and author of dozens of books and articles which have been extensively published across the world, in almost 30 languages. James, thank you for joining us today, and for our listeners who may not be familiar with your work, give us just a few more words about yourself and your background.

JP: I’ve been active, I was a student leader in Berkeley in the 60s, and I became very active in Latin America, combining academic work with political activism. I was involved with several social movements, including the rural landless workers in Brazil from 1992 until 2004, I was involved with the unemployed workers in Argentina from approximately 2000 to 2006, and other movements in Latin America. I also was very much involved in various academic activities, including my professorship, and as a visiting professor in various countries, including Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil, Greece, and Spain. I also was in China as a visiting professor at the Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and in Shanghai in the late 80s. So I am pretty much an internationalist. Also, I am involved in struggles in the United States, but mainly as a writer in the last 25 years, mostly engaged in writing on foreign policy and particularly on U.S. policy to Latin America. I’ve written several books on U.S. imperialism and its impact, in particular in the most recent period on Venezuela.

MN: You’ve also written extensively about Greece, especially in the past few years, over the course of the economic crisis, and in one of your pieces, you wrote about the three generations of the Papandreou family and their role in what you described as the “destruction” of the country. Talk a little bit about this and about the Papandreou family and what their impact was on Greece.

JP: I’m most familiar with Andreas Papandreou because he invited me to direct the Center for Mediterranean Studies in Athens. I was a personal adviser to him, particularly in 1982 and 1983, when we would meet once a week and discuss Greek politics. He was very flattering and congenial and he would take a notebook out, and one had the impression that he was taking serious policy recommendations, but in fact what he did was use a lot of leftist ideas to justify right-wing policies. I must say that in the first six months or year, it was very clear he wasn’t going for any kind of socialist transition, but I stayed because I thought we could at least create a political space, a platform, for the trade unions and the agricultural movements to advance and build up a grassroots movement which could push further. So I stayed in for about another year, and I saw very quickly that this was a clientelist regime, that he would always find excuses for not doing what he promised, beginning with the U.S. military bases, which he always claimed there was a “fakelo,” an envelope which he was about to reveal as the basis for his expulsion of the bases, which was all bluff. He was very cynical in his own way, about his balcony speeches and his capacity to mesmerize the masses while secretly or less conspicuously engaging with big business, the U.S. Embassy, and with NATO, and that was decisive in some ways for my questioning his government early. What precipitated my resignation was the expulsion of major trade union, socialist trade union leaders when they protested his stabilization program, and it was all done with his index finger.

There was no democracy, no discussions, it was a totally personalistic dictatorship in PASOK, and I saw Tsochatzopoulos and other cabinet members involved in all sorts of chicanery, bribe-taking, corruption, and other activities. After I left, it became much worse, not because I left but because PASOK was using a lot of the EU money to build up its clientele, to enrich its leaders and bankers. Frequently they gave loans to business people that had no intention to pay it back, but it was understood as a kind of bribe with kickbacks to leading PASOK members and to the PASOK treasury. This corruption and deception and conformity with NATO, with the EU, with big business, combined with the demagoguery and “koroido,” the fooling of the people, was endemic in Greece, and it was one of the factors that has ignited my criticism of SYRIZA, this idea of “koroido,” of saying one thing to the people and doing the opposite in practice, putting on theater with radical gestures for the domestic consumption, while agreeing to very insidious and reactionary policies with their overseas lenders, overseas associates in the EU and in NATO. And I think this a serious problem, among other things in Greece, among other factors, not only the corruption that’s endemic, the enrichment of the political elite, but the sense of being able to fool people, to engage them and mobilize them and then turn your back on them after securing office. I might say this is common practice among social democracy and particularly in the United States, as we saw with Obama promising peace and engaging in more wars than any other president, but you expect something different from a party that’s called itself socialist, a party that repudiates austerity and then puts it into practice. So I think this kind of phenomenon, the legacy of PASOK has found expression in SYRIZA, and it’s not accidental. Many of the corrupt people from PASOK joined SYRIZA when the ship was sinking, and Tsipras welcomed them. In fact, he appointed one of the most corrupt advisers to George Papandreou to be his minister of finance, Yanis Varoufakis. That should have rang some bells as to the real course that the government was going to undertake, and I think that it’s indicative that we can’t expect anything close to what SYRIZA represented itself as, particularly in the Thessaloniki program. It’s doing exactly the opposite, and it reminds me a great deal of Papandreou’s regime, PASOK’s regime. Tsipras seems to be a reincarnation of Andreas Papandreou.

MN: We are on the air with political analyst and professor James Petras here on Dialogos Radio and the Dialogos Interview Series, and James, when Andreas Papandreou was elected in 1981, aside from this rhetoric which you mentioned about Greece leaving NATO and kicking out the foreign bases from the country, there was also this rhetoric about leaving the European Union as well, and of course that did not happen either. How was the Greek economy transformed through membership in the European Economic Community, as it was known then, and later on of course, the European Union?

JP: I think there’s several things that have to be said. As I said, I was privy to the inner circles of Andreas Papandreou at that time. There was a report prepared on the consequences of Greek entry into the European Union. It was very negative, it pointed out that the grants and the financial transfers would be more than nullified by Greece’s inability to compete with the open market, and that Greece would be a subordinate partner in the EU and it would strategically have a very negative effect on the way in which the Greek economy transformed, given the fact that the European partners were much more powerful and much more competitive and much more likely to dominate Greek markets and reduce Greece to a tourist haven. Papandreou saw that report and rejected it. I know for a fact that there was a professor from Princeton whose name escapes me at this time, that did this cost-benefit analysis. Now, the end result was that in the short run, Greece received a lot of loans and what they called “competitive funds,” which were supposed to create Greek industry and agriculture and allow it to eventually become competitive with the European associates. Most of this funding went in to building up PASOK’s electoral base, particularly in the countryside. I have relatives that took the money and didn’t increase their efficiency, they built apartments for their married kid, their children, they sent them to college and they did a lot of things, but nothing to increase the competitiveness of agriculture, and that was general. The loans went to businessmen who laid the foundations of factories and never completed them. Greece remained a backward economy, and PASOK was able to build a machine in the same pattern that the right-wing had done, New Democracy was a very corrupt party, very clientelistic, even more authoritarian and repressive than any government in Europe at the time that claimed to be a democracy.

Now, the end result of this was that Greece was essentially a very uncompetitive economy. The Europeans didn’t care, because, though as a principle they did complain that there was corruption in Greece, they did complain about misallocation of funds, but they really understood that they had the levers of power, that the same people that lent them money could impose conditions, and more importantly, they constructed a structure, a political structure in which Brussels would dictate Greek policy. The strategic, long-term impact was that Greece lost sovereignty, Greece’s economy became utterly dependent on the Europeans, they had no fiscal flexibility or policy to adjust, to try to stimulate the economy and to reorient its trade if any opportunities arose, as they did in Asia and other countries. They were totally colonized, and during the expansion, particularly when they joined the European Monetary Union with Simitis, who I had encounters with when I was in Greece, completely submissive to the Brussels elite, and as a result of that, Greece had an artificial boom. The political oligarchs in both New Democracy and PASOK organized the Olympics, which was a huge boondoggle, billions of dollars of European money were spent on building stadiums which are growing weeds now, and contractors and bankers and everybody, including Goldman Sachs, which cooked the books so that the European Union actually believed, I think they believed that Greece was balancing its books and that it had no great debts and liabilities. This was totally falsified, and when the crash came, everything became null. Greece had not a competitive economy, Greece had enormous accumulation of unproductive debts, and that’s key. The money that Greece had borrowed was stolen. Bank loans were made to business people that were never expected to be paid. And so, the Greek people were saddled with debts which benefitted individuals and corporations that didn’t invest in Greece. They didn’t develop the capacity to pay back the debts. Huge tax evasion, all the leading PASOK leaders that I knew, none of them paid anything near their taxes, nor did the ship owners, nor did the bankers, nor did the small businessmen. When I was in Greece, we did a study of “mikromesaioi,” sort-of middle-class, lower-middle-class businessmen. They never paid any taxes or only a fraction, so it was endemic, it wasn’t just the oligarchy but it trickled down into the middle-class. No sense of civic responsibility and no enforcement, from either the right-wing or the center-left governments. As this was amassed, the European Union, as I said, overlooked this, because ultimately they held the levers of support. They allowed their funds to be misallocated because the trade-off was that they totally controlled Greek economic and social policy.

MN: We are on the air with political analyst and professor James Petras here on Dialogos Radio and the Dialogos Interview Series, and James, that brings us to 2009 and the “official” beginning of the economic crisis. This was also the year that George Papandreou was elected as prime minister of Greece. How did George Papandreou continue the job begun by his father and his grandfather, and how did the European Union, if you will, take advantage of this situation, this crisis that was unfolding in Greece?

JP: George Papandreou was the author of the sign-off of the “bailout” and the memorandum and the troika. He was involved with submitting Greece to the oversight of Brussels, of the transfer of sovereignty from Greece to Brussels, and the refloating of the Greek economy through loans which were recycled back to the banks. Essentially, what happened was that a lot of the Greek loans were to private companies, and George Papandreou, what he did was, he took loans to pay back private creditors, and therefore, most of the current Greek loans are to official international lending agencies like the European Central Bank, the IMF, and other public institutions. So what in effect happened was, George Papandreou signed off on the de facto and de jure control of the Greek economy by the troika, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the IMF. They essentially dictated policy, and he increased indebtedness to pay back past loans, private-sector loans, and he was instrumental in the massive social cuts, where they laid off and cut back on pensions and public employment and unemployment benefits, and it became very clear that he was the author of the social crisis. He was replaced in PASOK by Evaggelos Venizelos, who continued the policies and this line of continuity. So essentially, they were the instruments of the transition from a semi-sovereign country to a complete colony. Greece is a colony, it’s a vassal state, it has no control over economic policy, income policy, it’s lost and is in the process of losing all of its major lucrative public enterprises through forced privatizations. So essentially, they were the leaders of the recolonization of Greece.

MN: Earlier in the interview, you mentioned SYRIZA taking over this policy baton, if you will, from PASOK. There were many, of course, in Greece and in the global left who held high hopes for SYRIZA two months ago when they came into office. There’s many who still insist on giving the new government some time to prove itself, while there’s others who have become disenchanted. What is your view on SYRIZA and how they have performed in their first two months in office, and you mentioned Varoufakis as well…a lot of people have given him a lot of praise. How do you react to him?

JP: I think he’s a clown. I don’t think he’s a serious political figure, above and beyond the reactionary policies. Let me go back though and say this: any serious analysis of SYRIZA has to look at the various layers in SYRIZA and when they became part of SYRIZA. Originally you had Marxist and radical groups, small groups, that came together, Euro-communists, moderate leftists, and other radical leftists. Some of them with some assertion in the mass struggles, but mostly small groups that had a marginal influence on the mass movements. Subsequently, they began to attract the popular vote, middle-class, lower-middle-class salaried people, and as they grew, they began to attract support from two directions. One, from the unemployed youth, which was involved in the major riots against the killing of one of their schoolmates, and growth of some trade union support, especially from the communist party, but also, as PASOK sank from 40-something percent to ten percent or twelve percent, they began to attract PASOK leaders and people that are involved in the political apparatus, including Varoufakis, who had a very negative background, and if you look back to 2004, 2005, 2006, he’s really a bootlicker, running interference for George Papandreou. Nobody studied that different layers that came in, the opportunists that joined SYRIZA. They just looked at the program, which the left formulated but the leadership and direction was in the hands of these opportunists, middle-class politicians, totally disassociated from the general strikes and mass struggles. So there’s a kind of separation between the radicalizing mass movements and the kind of antecedents that a good section of leadership had. One other factor was that Tsipras, like Papandreou, developed a style of leadership which was very much a caudillo, in Latin America, personalistic leadership, increasingly authoritarian, dictating policy and then explaining it afterwards. There were factions in SYRIZA, some claiming to be more leftist than others, but Tsipras and his inner circle, mainly people like Varoufakis from the right wing of the party, have nothing to do with socialism, it’s a joke hearing Varoufakis talk about himself as some kind of dissident Marxist. There’s absolutely zero Marxism, absolutely zero in terms of any commitment or engagement in the mass struggles, and these people were increasingly decisive as the elections concluded, in seizing power and dictating policies. And they’re very conscious of the fact that they are in total contradiction. When SYRIZA gathered the votes, the first thing they did was recognize the debt. There was absolutely no questioning of the illegality. I would say that 90% of Greece’s debt was originally contracted by kleptocrats, and they should have never paid that debt. In the case of Ecuador, they had a commission before they paid a cent, and showed that about 75% of the money went to the Ecuadorian elite and out of the country. I’d like to know how much of the loans went into personal accounts and overseas real estate by the recipients of those debts. So they didn’t question the debt, they put on theater and there was laughter outside of Greece, in the European press, the financial press, about the theatrics of Varoufakis making these radical noises and then capitulating on every count, running from Paris to London on bended knee asking for support.

Of course the people saw these very submissive and demagogic people that made no preparations for capital flight, they made no preparations for confronting the intransigence of the Europeans. Why should the Europeans renounce the debt when Greeks were accepting it, when SYRIZA was accepting it? It was absolutely clear, within two weeks, who was in control in SYRIZA, and nothing to do with the mass struggles. They saw people who were absolutely committed to staying in the European Union despite the fact that the European Union is run as an elite club dictated by Germany, and expecting, somehow, these power elites to sacrifice their interests when they have a submissive leadership that didn’t organize a single general strike or protest or mass mobilization when they confronted these people. They thought that their cleverness, their occasional banging of the table, would result in something. Let me give you one example: when I was in Hungary in the 90s, they had a similar problem of negotiating with the IMF, and I was with the minister of economy at the time, this ex-communist social democrat, and outside his office was a huge demonstration, and he winked at me and he said “while I’m negotiating with the IMF, I tell them look, if you don’t deal with me, you’re going to have to deal with them, there’s 100,000 people outside.” And he clearly engineered the mass protest as a lever on negotiations, to secure some concessions, postponement of payments, etc. SYRIZA didn’t do that, wasn’t even clever enough to put their strength in front of their negotiation. They were amateurs, they were people that didn’t understand that when you announce you’re going to attack capitalism, you don’t lower your gun, you begin to take measures expecting them to retaliate. They’re going to retaliate, and SYRIZA made no attempt at any point, apart from opportunist and conciliatory gestures, they didn’t even mobilize their strong side, didn’t even take any precautions against the flight of capital, did nothing to maintain their fiscal financing. They announced the tax concessions before they had calculated what consequences there were, a property tax on the middle-class and upper-middle-class. So it was a political movement without any kind of political will, political mobilization, political capacity to understand the nature of power when you’re dealing with adversaries.

MN: We are on the air with political analyst and professor James Petras here on Dialogos Radio and the Dialogos Interview Series, and James, you were an adviser to other left-wing leaders, including Salvadore Allende in Chile and to Hugo Chavez prior to his death. What was your experience in working with these leaders and what was their vision for their countries in the face of United States hegemony, and how do they compare to what we’ve seen in Greece?

JP: First of all, Allende was a consequential democratic socialist. When I was in Chile, we were very clearly involved in agrarian reform, expropriating the giant copper companies, the banks, and pushing for deepening that process, turning it from nationalized public enterprises into worker-controlled enterprises. That government in Chile was an arena from which one could fight from inside, because you’re fighting within a process of transformation. My biggest criticism was the fact that they made no effort to support the progressive military generals, and that’s when I left Chile, a few days before the coup, when I saw that the carelessness of the government in dealing with a strategic issue like military power and the fact that the military in Chile was divided and that the pro-U.S., pro-coup faction was gaining ascendency without any effort to arm the workers, which was on the agenda. I want to say that tactically we were very successful and strategically it was a failure, in the sense of the military question. By the way, I did raise this with Papandreou when we first got together in November of ’81, right after he was elected. I was in Italy at the time and I flew to Greece and I asked him about the military question. He said “well, I’m retiring 39 generals.” I asked “what about the 40th,” and he said “he’s another fascist.” So he was aware of issues, but unable or unwilling to deal with them in that sense.

With Chavez, the issue was not compatibility, ideologically and in terms of interest. He read my books, we discussed them a couple of times, and I emphasized to him that his welfare policies were all well and good and were very important in arousing electoral support and mass mobilization, but he had to move on diversifying the economy, that an oil-based economy is not a sustainable basis for long-term growth, that the oil boom, sooner or later, was going to end, and then what? How would you finance? Also, the security question, that they were allowing these NGOs which were conduits for U.S. intervention in Venezuela, and which should be closed down. Again, there was agreement and then nothing happened, so you feel a bit self-important, look, I’m influencing the government, but really, we weren’t influencing the government in that sense. We had to build socialism on a one-crop economy, and that’s true in Cuba and that was true in Venezuela.

So, the difference with SYRIZA is, you’re talking in Venezuela and Chile with a government that’s in the process of transformation, so you feel that you have a common ground, that there’s a huge welfare program in Chile, there’s a big transformation of property relations, increasing control of revenues of oil and going back into the country at least and raising living standards. That’s not the case in Greece. There isn’t a common basis, there isn’t a sense in which power is changing from Brussels to Athens, that the privatizations are not going to be continued and the previous privatizations, illicit and corrupt, are going to be reversed. There isn’t a minimum basis to say “well, we’re sharing something that we need to go forward with.” There’s nothing that you can say that SYRIZA has done, not even this minimal thing, with the cleaning women and the finance ministry, that SYRIZA demagogically suppressed, that what they were going to do when they came to power is to rehire these women. Well, they’re still living in the tents outside the finance ministry. Even the few hundred thousand euros that would put these women back to work, they have said “tha to kanoume,” “we will do it.” Everything is “we will,” “tha.” It’s the faux socialism of the later Papandreou. And might I even say this: the first year of the Papandreou government, we passed a lot of progressive, redistributive, income-increasing policies, raised the minimum wages, extended trade union bargaining, legalized divorce, and other gender issues, built universities, extended the national health plan, etc. So at least, I felt, there was still a basis to say “well, these are not socialism but they are positive steps that strengthen the mass movement, so I’m staying.” Once it was clear that they were things that were meant to be reversed, that the negatives far exceeded the positives, then that was the point at which a rupture took place. But SYRIZA is not even anywhere near these moderate reforms that PASOK passed in its first year in government, that is in 1982-83.

MN: James, in wrapping up, what policy actions do you believe Greece and a hypothetical government should undertake in order to break free of the crisis and this ongoing cycle of austerity?

JP: It’s very difficult at this point to see. I think the opportunity was, when they first came in, to put in capital controls, to stop the run of money, to begin to collect the taxes and cutting off debt payments. I think still that is the agenda that needs to be pursued. It’s going to be harder, it’s going to have more serious internal reprecussions, but I think Greece cannot continue paying the debt. There’s no money for the debt, and any minimal kind of immediate payments, salaries and pensions, and I think secondly, I think they cannot continue making these regressive concessions that the European Union calls “reforms.” That absolutely has to stop. They have to build an emergency economy. They have to renounce the debt payments immediately. They have to impose capital controls. They have to look to finding alternative forms of raising revenue, using social security funds, etc. It’s an emergency situation, I think they have to put the country on a war economy, they have to convoke mass meetings and explain to people, make self-criticism, explain the mistakes they’ve made and how they’re going to proceed in rectifying them. They cannot operate with Varoufakis taking photos, holding champagne drinks in his penthouse overlooking the Acropolis, and then talking to the masses how he feels about poverty. This kind of bull****, this kind of theatrical lying and deception that goes on has to stop.

MN: Well James, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us today here on Dialogos Radio and the Dialogos Interview Series.

JP: It’s a pleasure.

Please excuse any typos or errors which may exist within this transcript.